eth2 was a rollup format

2020.10.02 -When we transition to a new scaling paradigm, it is good practice to review what we've left behind.

The goal of this post is to convince the reader that a "rollup-centric" approach is not a major departure from sharding and hopefully build a more intuitive understanding of the (hypothetical) system as a whole.

Definition of an Optimistic Rollup

For the purpose of this post, let's specify only the most simple implementation of an Optimistic Rollup (ORU).

Let an ORU have the following properties:

- All transaction data is submitted on-chain

- The state root is submitted on-chain

- The state root is accepted optimistically

- There are some nodes that validate the ORU's transitions

- There exists a fraud proof executor on-chain that can revert an invalid transition

Impossibility Result of Sharding

Before proving that eth2 sharding is just a complex system of ORUs, let's first examine why naive sharding isn't the solution to safe scalability. The reason is not particularly intuitive at first.

Mathematical Security of Sharding

Let's assume there exists a blockchain with 16,384 validators, 64 shards, and 128 committee members validating each shard. There is no committee selection look-ahead and after each slot all committees are disbanded and 64 new committees are determined randomly from the overall validator set such that no validator knows what committee another validator is on. Assuming a (i.e. 86 committee members) quorum is required to progress a shard, this implies the probability of a malicious committee chosen at random, without replacement, from the validator set with byzantine validators is:

.

It should also be noted that this parameter can be scaled up and down by modifying the committee size to achieve the desired level of security.

Between the negligible chance of a malicious committee being assembled and disincentives for being lazy, this sharded system should inherit the safety and liveness guarantees of it's non-sharded coordinator. But like most real world systems, it isn't so simple. Committees are known ahead of time, leaving room for adaptive adversaries to bribe rational participants into performing arbitrary behavior. This is even more prevalent, if a mapping from validator public keys to IP address can easily be created. Moreover, verifiable voting in permissionless settings is inherently vulnerable to bribery. For these reasons, the real security of the shards is at least an order of magnitude worse than the theoretical values.

Sharded Data Availability is Plasma

Even if the security of the shards is less than the overall protocol, we can still ensure safety by allowing fraud proofs to revert invalid transitions. However, without additional modifications to our hypothetical sharded chain, its possible for an adversary to not release enough data to ever generate such a fraud proof -- therefore forcing community intervention. We'll show how this attack can be carried out.

Let's assume a naively sharded blockchain with shards and . The blockchain runs a traditional BFT consensus algorithm which facilitates committees to operate shards and , referred to as and respectively. Each block in base chain includes threshold signatures consisting of members from and attesting to the current block root for their shard.

Assuming each shard is able to process the same amount of data and transactions per second as a non-sharded system, introducing them should provide approximately two times the throughput. In the optimistic case this is true.

Now let's execute the data unavailability attack on our construction. Assume a malicious entity is able to coerce of the committee members in to sign an invalid state root and to not publish the input data for that block on . The invalid root is then included in the next block in . There are no reasonable mechanisms that will allow to return to a good state. We can enumerate a few options:

- The minority in can raise an alarm on claiming data unavailability. Unfortunately this is a non-uniquely attributable fault and therefore, is unable to determine which group acted maliciously. This creates a free DDoS vector for a byzantine minority to exploit.

- The rest of the nodes in the network could raise an alarm that the data was not made available. Except they can't, because only the members of were watching during the fault.

- The community will realize that a fault occurred and roll back to its last known good state. This is bad for obvious reasons.

- A Plasma-like mass exit from to is performed, incurring all its negative properties.

Like in Plasma, the real problem here is data availability.

Safely Increasing Data Availability

Hopefully the pathological case above is enough to convince you that our focus should first be directed at scaling data availability on the base layer. Otherwise, the system will continue to be susceptible to data unavailability attacks.

Traditionally, improving the data throughput on a blockchain required out-of-band agreements on the minimum supported hardware / bandwidth requirements of the system -- implying a certain acceptable blocksize. Recent work by Mustafa Al-Bassam and Vitalik Buterin provides a probabilistic mechanism to ensure data availability. This work was further extended by M. Yu et al. with their Coded Merkle Tree accumulator, which provides order-optimal metrics.

The key insight to these schemes is the relaxation of the requirement that participants in the network download all the data. Instead, Vitalik proposed that participants in the network randomly sample small chunks of the block to ensure that the proposer has made the data available. The danger is that the block proposer only needs to hide a small amount of data to carry out a data unavailability attack. Therefore, participants must sample the block many times in order to gain enough confidence to accept the block as available. To reduce the number of samples, Vitalik proposed to encode the block data with a two-dimensional Reed-Solomon encoding.

In this construction, the block chunked into shares and then encoded, generating shares where any out of shares can reconstruct the block. Assuming , then the block proposer would need to hide of the block in order to successfully execute a data unavailability attack. The Coded Merkle Tree offers a similar construction, but with decoding overhead and hash commitment instead of decoding overhead and hash commitment offered by 2D Reed Solomon encoding, where is the size of the block in bytes.

For a more detailed explanation of this technique, please see this note.

Shards are Rollups

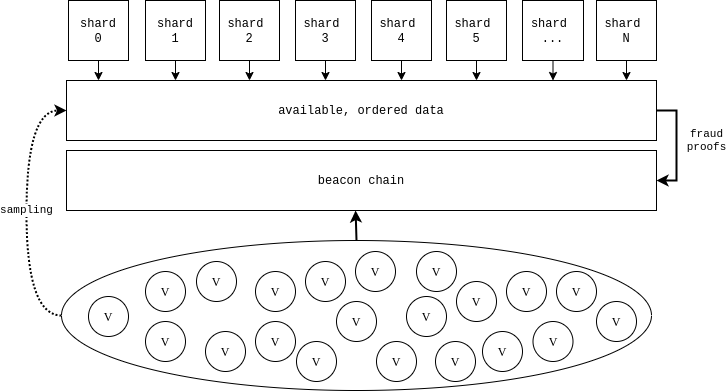

The sharding design in eth2 obfuscates the fact that they are actually just ORUs to the beacon chain. If the focus is shifted from distributed processing to the ordered data availability layer, it becomes clearer.

In the diagram above, the validator set has four roles:

- Validate and execute the beacon chain

- Sample the data made available by the shards

- Serve on shard committees

- Submit fraud proofs for invalid state transitions

Since we've made the assumption that the data will either i) be available or ii) the chain will fork to last point where data was available, a fraud proof will either be able to be constructed or the system will attribute the lack of data availability to the shard quorum who signed the block and rollback the transition.

By Definition, Eth2 is an ORU

At this point, we should be able to prove that the shards are in fact rollups -- given our earlier definition of an ORU:

1. All transaction data is submitted on-chain

Shard block data is pooled into the data availability layer, verified by the entire network probabilistically.

2. A state root is submitted on-chain

Shard committee attest to shard state roots which are included in beacon chain blocks.

3. A state root is accepted optimistically

The beacon chain optimistically accepts shard committee attestations without additional validation.

4. There are some nodes that validate the ORU's transitions

The shard committees validate the shard transitions.

5. There exists a fraud proof executor on-chain that can revert an invalid transition

The beacon chain supports shard transition fraud proofs.

Deconstructing Eth2

Now that we've shown the uncanny similarity between eth2 and a system of ORUs, how can we use this information to better understand the design of the overall system? Let's explore a few design decisions made in eth2 through the lens of a system of ORUs:

Data Throughput

In the current design, the system's data throughput is tightly coupled to shard mechanics.

An approach that could be taken here is to treat data availability checks as a first class citizen in the protocol. This will allow the data layer to be optimized independently, and for the execution layer to have more granular control over hardware requirements.

For example, instead of shards eth2 could offer 64 data hubs and an ORU contract on the beacon chain. The ORU contract could allow for rollups to decide on a leader election mechanism, how many hubs they wish to post data to, if they wish to atomically bind themselves to another rollup (e.g. if one rolls back, they also roll back). The more hubs in use, the higher the hardware requirements to validate the rollup would have to be.

The system described above would be a strict superset of the current sharding design. Not only could there still be 64 protocol defined shards, there could be other rollups with their own characteristics built on top of the secure data layer that are not bound to the fate of the protocol shards.

Rollback Minimization

In a simple ORU, the elected leader has the power to submit an invalid state transition. Although this isn't a safety violation, because a fraud proof will revert the transition, it does disrupt the progress of the rollup. In isolation, this disruption is typically not worth the cost for an adversary. However, in eth2, cross-shard communication makes this problem particularly thorny. Shards on slot have the expectation that they can build off of all other shard states at . If some shard crosslinks an invalid state transition, there is no reasonable way to revert its side effects on shards where other than a unilateral rollback.

To avoid such a catastrophic event, there must be mechanisms in place to avoid such rollbacks. Two obvious ones are shard committees and custody bit checks. As demonstrated in the section above regarding the mathematical properties of sharding, the chances of corrupting of a shard committee are low -- even taking into account the various attack vectors. The custody bit helps ensure that honest validators aren't duped into signing an invalid transition out of laziness.

By viewing these mechanisms as deterrents against invalid transitions, instead of mechanisms upholding the safety of the system, we have the ability to choose parameters that may make more practical sense while achieving the same effect. For example, reducing the shard committee size to 64 members will still yield a probability of of randomly sampling a byzantine committee. But from a practical networking and signature aggregation point of view, it could significantly alleviate some of the burden.

A Rollup-Centric Ethereum Roadmap

This post was originally written during SBC20 when I begun to fully grasp the similarities between eth2 and ORUs. In light of Vitalik's post, I decided to finally publish this post in agreement of the "rollup-centric" approach for the future of Ethereum. Although, as shown in this post, a "rollup-centric" approach is not a major departure from where we were already heading -- just a superset. The problems we faced with sharding are isomorphic to problems we'll face when integrating cross-rollup communication. This means that the large body of work that has already begun on the topic can continue, mostly uninterrupted.

The rollup-centric roadmap will reduce the protocol complexity that would be required to shard execution. It will allow us to develop complex, shard-like rollup mechanisms iteratively. This will enfranchise a much wider set of developers to contribute different rollup formats and allow existing core developers and researchers to focus on building a robust data-availability layer.

One could say that the path to a fully-functional eth2 has never been clearer.

--

If you found this interesting and want to discuss the topic further, contact me on twitter @lightclients. I'm also looking to connect outstanding researchers & engineers to impactful projects. DM me if you'd like help.